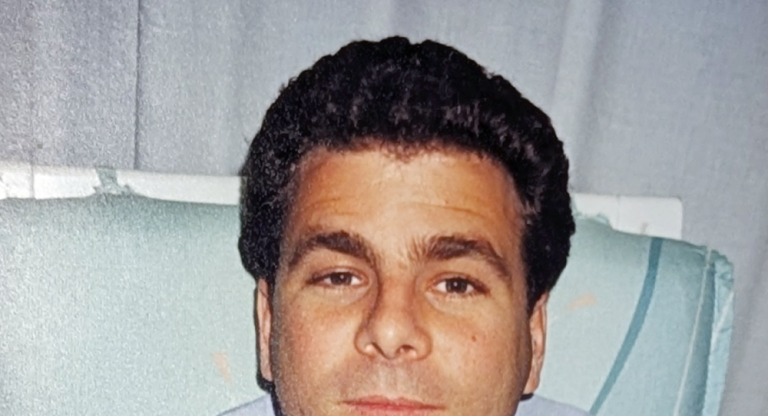

Dr. Erin Bearss: Leading the charge through the pandemic and beyond

Dr. Erin Bearss’ early ambitions were otherworldly. She aspired to be Agent Dana Scully - portrayed by the incomparable Gillian Anderson - from the hit 90s TV series The X-Files. But unlike Dana Scully, Dr. Bearss wasn’t interested in pathology: she was interested in caring for people. That’s how she found herself pursuing a career in both family and emergency medicine. For the last two decades, Dr. Bearss has been practicing medicine at Sinai Health and is now Family Physician-in-Chief of the Ray D. Wolfe Department of Family Medicine, at Mount Sinai Hospital.

From the very start of the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Bearss has been at the helm of Mount Sinai Hospital’s COVID-19 Assessment Centre and many of its vaccination initiatives. “We were running towards the crisis while everyone else was running away, and we were basically fueled by adrenaline,” says Dr. Bearss. But adrenaline eventually plummets and you’re left with a stark reality: it’s a pandemic, people are scared, and there are many unknowns. “We were constantly improving our processes to meet the needs of our community, opening to staff then community members. In the beginning, people were stressed, the lines at the assessment centre were so long.” A solution to this problem was found when the lines at the assessment centre were replaced with appointment slots which was much better for patients and for staff. But if it’s not one thing it’s another - the ebbs and flows of the pandemic’s waves, vaccine shortages and snowstorms are just a sampling of the hills that health-care workers have had to climb over the past two years.

Despite change and exhaustion being the only constants during this pandemic, there have been bright spots. “It’s been such a positive experience. Employees and physicians from every area and department of the hospital said, ‘put me in, coach’, and that was amazing to see.” The all-hands-on-deck attitude helped get needles in the arms of some of the community’s most vulnerable people as soon as vaccines were available. “Our people were willing to go anywhere to help - all over the city. Physicians and nurses from almost every department- surgery, medicine, OB, pathology, radiology, family medicine, psychiatry, anaesthesia - the list goes on. Anyone trained to provide vaccines was volunteering. It was inspiring to see everyone come together and make something incredible happen.”

While COVID-19 has demanded a great deal of Dr. Bearss’ time, her commitment to other areas of health care has never wavered. One of those passions is delivering accessible care. Dr. Bearss champions a medical approach that is informed by a person’s lived experience. As part of this focus, she introduced a new role at Mount Sinai Hospital’s Family Medicine Department: Faculty Lead, Social Accountability, Equity, Diversity and Inclusion. Dr. Bearss’ goal is to drive the family medicine department forward clinically and academically, but that forward momentum isn’t just defined by medical success. It’s defined by equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI). “We use an EDI lens on everything we do. From the emails we send to renovating our waiting room, we ask ourselves: is this inclusive? Is it accessible? If not, how can we use inclusive language, or make a space barrier-free?” says Dr. Bearss. “Ensuring we are inclusive means listening to our patients, giving them a voice at the table as partners in their care.” And this approach isn’t limited to Family Medicine. Dr. Bearss brings it to the emergency department, as well. “There are things that simply aren’t a priority because no one has made them a priority. Take medical equipment, for instance. We might use a device on women that’s less comfortable for them when there is a better option, I’m just one of a few people highlighting these issues so that we can make these changes now.”

For health-care professionals, family medicine has made great strides in terms of EDI. But there is still a long way to go before it can boast a truly equitable, diverse, and inclusive framework, as outlined in this article from Rebecca Renkas. Dr. Bearss notes: “Women have been well represented in Family Medicine for the duration of my career, but there are gaps.” As of 2019, 47% of family physicians were women, compared to just 11% in 1978. And nearly 60% of family physicians under the age of 40 in Canada are women. More women entering family medicine is a good thing: they generally spend more time with their patients, are thoughtful when prescribing medication and are better at treating mental health issues. But for all the same reasons women make excellent family doctors, they get paid less than their male counterparts since remuneration is based on the number of patients you see, not the quality of the care provided.

Despite the persistent gender pay gap, Dr. Bearss is a self-purported optimist. “I’m a glass half-full kind of person. Even when things are stressful and challenging, I try to stay positive. I’m a problem solver so I just keep trying to seek solutions to the problems,” she says. There’s no toxic positivity in her approach. Rather, a stubborn determination that drives her to create the good she sees so much potential for. “What I tell people, especially women, getting into medicine is to decide what you want to do, pursue it and troubleshoot the obstacles as they come up. Don’t pick a path because it appears easier or someone tells you it’s what you should do. It might seem simpler because of unwritten or unspoken rules - social norms - that lead you to believe you can’t do something. Most of the time these rules are perceived but not necessarily a reality, and you can absolutely achieve your goals. Just keep persevering.”